Health Care Around the World

Author and Page information

- This page: https://daihochutech.site/article/774/health-care-around-the-world.

- To print all information (e.g. expanded side notes, shows alternative links), use the print version:

Health provision varies around the world. Almost all wealthy nations provide universal health care (the US is an exception). Health provision is challenging due to the costs required as well as various social, cultural, political and economic conditions.

There isn’t one answer to health care provision, but a number of systems and issues seem to be emerging. This page provides a high level overview.

On this page:

The health care challenge: services for those with need

The World Health Organization (WHO) is the premier organization looking at health issues around the world. When looking at the pattern of health care around the world, the WHO World Health Report 2008 found some common contradictions (see p.xiv, Box 1):

- Inverse care

- People with the most means – whose needs for health care are often less – consume the most care, whereas those with the least means and greatest health problems consume the least. Public spending on health services most often benefits the rich more than the poor in high- and low-income countries alike.

- Impoverishing care

- Wherever people lack social protection and payment for care is largely out-of-pocket at the point of service, they can be confronted with catastrophic expenses. Over 100 million people annually fall into poverty because they have to pay for health care.

- Fragmented and fragmenting care

- The excessive specialization of health-care providers and the narrow focus of many disease control programs discourage a holistic approach to the individuals and the families they deal with and do not appreciate the need for continuity in care. Health services for poor and marginalized groups are often highly fragmented and severely under-resourced, while development aid often adds to the fragmentation.

- Unsafe care

- Poor system design that is unable to ensure safety and hygiene standards leads to high rates of hospital-acquired infections, along with medication errors and other avoidable adverse effects that are an underestimated cause of death and ill-health.

- Misdirected care

- Resource allocation clusters around curative services at great cost, neglecting the potential of primary prevention and health promotion to prevent up to 70% of the disease burden. At the same time, the health sector lacks the expertise to mitigate the adverse effects on health from other sectors and make the most of what these other sectors can contribute to health.

Health care provision is incredibly complex and many nations around the world spend considerable resources trying to provide it. Many other rights and issues are related to health, inequality being an important one, for example. Education, gender equality and various other issues are also closely related. Viewed from the spectrum of basic rights, the right to health seems core.

Health as a human right

As noted by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the WHO,

The right to health is relevant to all States: every State has ratified at least one international human rights treaty recognizing the right to health. Moreover, States have committed themselves to protecting this right through international declarations, domestic legislation and policies, and at international conferences.

The above fact-sheet also provides a useful breakdown of different aspects of rights to health, describing the relationship between health and

- Inclusive rights,

- Freedoms (from non-consensual medical treatment, from torture and other cruel or degrading treatments or punishments)

- Entitlements (to prevention, treatment and control of diseases; access to essential medicines; maternal, child and reproductive health; health-related education; participation; timely services)

- Non-discrimination

- Accessibility, acceptability and quality of services.

A wide range of factors, or determinants of health

allow us to lead a healthy life, including

- Safe drinking water and adequate sanitation

- Safe food

- Adequate nutrition and housing

- Healthy working and environmental conditions

- Health-related education and information

- Gender equality.

Human rights in many of the above areas therefore also overlap with health-related human rights as also represented by this WHO diagram:

Based on these and related principles, most nations strive for universal health coverage.

Universal Health Care

Universal health care is health coverage for all citizens of a nation.

Does provision of universal health infringe on individual human rights? Some argue that a universal system requires some level of transfer of wealth from those who have to support those who have not. Any such transfer infringes on the freedom of the individual being taxed.

Others argue that providing access to health enables one to enjoy freedom, and as a society it is a shared responsibility (much like sharing the burden of funding a military or providing education for all). As such, social equity and individual freedom do not necessarily have to conflict. (See also this site’s section on poverty and inequality for more about the effects of inequality on all of society.)

At some point the debate becomes ideological rather than practical, and most nations that attempt universal health care, while often supporting individual freedoms see value in a society generally being healthy.

There are numerous ways such a system is provided, for example:

- Government funded (tax paid) national systems

- Government funded but user fees to top up (often at point of use)

- Health insurance systems (funded by governments, citizens, or some mixture)

- Decentralized, private systems run for profit or not for profit

Different parts of the world have used different means for health care and generally, poorer nations have struggled to provide adequate health care.

Structure of a health service

At a high level, health services fall into different categories of health care:

- Primary health care

- Secondary health care

- Tertiary health care

(Some systems may also have additional levels of separation.)

Primary health care

Primary care is usually the first point of contact for a patient. Primary care is typically provided by general practitioners/family doctors, dentists, pharmacists, midwives, etc. It is where most preventative health can be achieved and where early diagnosis can be possible, which may prevent more expensive hospital treatment being required.

By its nature, primary care involves communicating with patients, developing personal connections with patients, going out into the community, using outreach programs for promoting good health and preventative strategies, and more. As such, it can often be extremely cost-effective.

For example, the World Health Organization estimates that better use of existing preventive measures could reduce the global burden of disease by as much as 70%.

In addition,

Primary health care also offers the best way of coping with the ills of life in the 21st century: the globalization of unhealthy lifestyles, rapid unplanned urbanization, and the ageing of populations. These trends contribute to a rise in chronic diseases, like heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes and asthma, that create new demands for long-term care and strong community support. A multisectoral approach is central to prevention, as the main risk factors for these diseases lie outside the health sector.

The following table summarizes some differences between primary health care and conventional health care:

| Conventional ambulatory medical care in clinics or outpatient departments | Disease control programs | People-centered primary care |

|---|---|---|

| Source: Primary Health Care, Now More Than Ever WHO World Report 2008, p.43 | ||

| Focus on illness and cure | Focus on priority diseases | Focus on health needs |

| Relationship limited to the moment of consultation | Relationship limited to program implementation | Enduring personal relationship |

| Episodic curative care | Program-defined disease control interventions | Comprehensive, continuous and person-centered care |

| Responsibility limited to effective and safe advice to the patient at the moment of consultation | Responsibility for disease-control targets among the target population | Responsibility for the health of all in the community along the life cycle; responsibility for tackling determinants of ill-health |

| Users are consumers of the care they purchase | Population groups are targets of disease-control interventions | People are partners in managing their own health and that of their community |

For more information on primary care and its importance, see the following:

- Primary Health Care section from the WHO web site

- WHO World Health Report 2008, which focuses on primary health care.

Secondary health care

In most countries this is usually when a primary care person such as a doctor refers a patient to a specialist.

Secondary care providers typically do not have the type of continuous contact with patients that primary care providers do, but help address more complex conditions.

Tertiary health care

This is specialized consultive care, often hospital care.

People often talk about building schools and hospitals, especially when it comes to aid and charity for poorer regions and countries. While hospitals are no doubt important, they give politicians and organizations more credence as they offer visible and tangible results (to their stake holders, such as tax payers and donors).

However, sometimes strengthening and improving primary care can often provide more effective health care (while also easing the burden on secondary and tertiary care). While this may be better for recipients, especially in poorer countries, it is also harder to measure and so often gets neglected.

The WHO, in the above-noted report, has tried to reiterate the importance of primary health care in health care systems.

Health provision overview in numbers

Shown here are just a few health related statistics. (See sources for more data.)

Child mortality is a general indicator of health in rich and poor country alike. Life expectancy, while a useful indicator, can also include deaths caused by accidents and the like, so healthy life expectancy

is also included:

Life expectancy

Predictably, wealthier nations have better life expectancy:

Note, healthy life expectancy is an estimate of how many years they might live in good

health.

Child mortality

Overtime, child mortality has generally improved around the world:

However, the gap is large between developing and wealthy nations:

Raw data

| Country/ group | Life expectancy | Healthy life expectancy | Infant mortality rate | Child mortality rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2008 | 1990 | 2000 | 2008 | 1990 | 2000 | 2008 | |

Source: World Health Statistics 2010 report, WHO Note, healthy life expectancy is an estimate of how many years they might live in | ||||||||

| Global | 68 | 59 | 62 | 54 | 45 | 90 | 78 | 65 |

| Low income | 57 | 49 | 101 | 88 | 76 | 158 | 137 | 118 |

| India | 64 | 56 | 83 | 68 | 52 | 116 | 94 | 69 |

| Lower middle income | 67 | 61 | 64 | 55 | 44 | 91 | 78 | 63 |

| Upper middle income | 71 | 61 | 37 | 26 | 19 | 45 | 32 | 23 |

| China | 74 | 66 | 37 | 30 | 18 | 46 | 36 | 21 |

| High income | 80 | 70 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 8 | 7 |

| Australia | 82 | 74 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 5 |

| Canada | 81 | 73 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 6 |

| France | 81 | 73 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| Germany | 80 | 73 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| Japan | 83 | 76 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 3 |

| Sweden | 81 | 74 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| UK | 80 | 72 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 6 |

| USA | 78 | 70 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 8 |

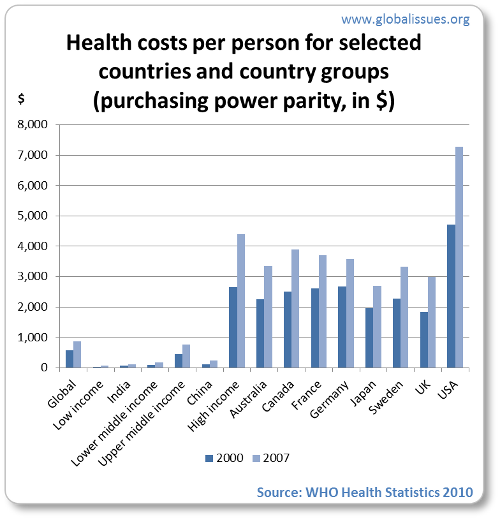

Spending figures show roughly how different regions fare:

Costs per person

(Note that the costs are calculated in purchasing power parity (PPP) which is a method to provide equivalence between different countries, so that $1 spent in India, for example, would go as far as $1 spent in the US.)

Spending as % of GDP

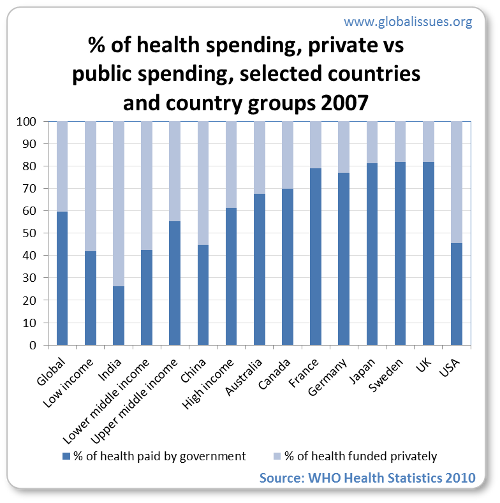

Spending sources

Note that private sources include external resources such as foreign aid, social security expenditure, out of pocket expenditure, private prepaid plans.

For low income countries, external resources are a major source of funds, some 17%. As per the 2009 WHO report (p.107), some 85% of private spending comes out of pocket (i.e. at point of use), which for the poorer countries is an enormous cost for individuals and does not allow the pooling of risk and leads to a high probability of catastrophic payments that can result in poverty for the household.

Raw data

| Country/ group | Total health spending as % of GDP | % of health paid by government | Health spending as % of total government spending | Health spending per person (PPP $) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Source: World Health Statistics 2010 report, WHO. (Note, some columns omitted to fit the available space. Please see source for full data.) | |||||

| Global | 8.7 | 59.6 | 15.4 | 863 | |

| Low income | 5.3 | 41.9 | 8.7 | 67 | |

| India | 4.1 | 26.2 | 3.7 | 109 | |

| Lower middle income | 4.3 | 42.4 | 7.8 | 181 | |

| Upper middle income | 6.4 | 55.2 | 9.4 | 757 | |

| China | 4.3 | 44.7 | 9.9 | 233 | |

| High income | 11.2 | 61.3 | 17.2 | 4,405 | |

| Australia | 8.9 | 67.5 | 17.6 | 3,357 | |

| Canada | 10.1 | 70.0 | 18.1 | 3,900 | |

| France | 11.0 | 79.0 | 16.6 | 3,709 | |

| Germany | 10.4 | 76.9 | 18.2 | 3,588 | |

| Japan | 8.0 | 81.3 | 17.9 | 2,696 | |

| Sweden | 9.1 | 81.7 | 14.1 | 3,323 | |

| UK | 8.4 | 81.7 | 15.6 | 2,992 | |

| USA | 15.7 | 45.5 | 19.5 | 7,285 | |

The following trend is also interesting:

(This trend also applies if plotting life expectancy instead of healthy life expectancy. The former is a cruder measure but easier to estimate than healthy life expectancy.)

There are many, many more statistics at the WHO statistics web site. The above charts were created from data obtained in the World Health Statistics 2010 report.

Health care in wealthy countries

All industrialized nations, with the exception of the United States, implement some form of universal health care.

Universal health care in all wealthy countries (except US)

The main ways universal health care is achieved in wealthy nations include:

- Government run (tax funded) systems, e.g. Britain’s NHS

- Privately run but the government pays most of it, e.g. Canada and France

- Private insurance companies but with regulation and subsidies to ensure universal coverage and non-discrimination by insurance companies (can’t deny based on medical history or existing conditions), e.g. Switzerland

The US and Health Care

The US is the only industrialized country that does not have universal health care for all its citizens.

There are programs for the elderly, military service families, the disabled, children and some poor through programs such as Medicare, Medicaid and so on, but some 45 million Americans go uninsured each year while another 25 million Americans go underinsured

. With the worsening global financial crisis hitting America hard, more are likely to lose medical insurance which is often associated with a job.

The US does, however, through Federal law provide public access to emergency services, regardless of ability to pay. However, the emergency services system has sometimes felt strain due to patients being unable to pay for emergency services and many who cannot afford regular health care either use emergency services for treatment, or let otherwise preventable conditions get worse, requiring emergency treatment.

The New York Times reports that life expectancy disparities are mirroring the widening incoming inequality in recent decades. Other health issues that are pronounced in the US, such as obesity, high cost of medical drugs, lack of access for large numbers of people, have been concerns for many years.

The US has not seen health as a human right, but as a privilege. However, President Barack Obama has tried to challenge this view, with proposed reforms to provide universal health care through health insurance for all. This has been met with wrath from the right wing, even though—as the charts above show—the US spends the most per person (in the world) on health care, yet does not get the best for all that money; most other industrialized nations get better, faster and cheaper health care.

In the previous link, author and former Washington Post reporter, T.R. Reid, looks at 5 myths that many Americans have about health care around the world and concludes:

In many ways, foreign health-care models are not really

foreignto America, because our crazy-quilt health-care system uses elements of all of them. For Native Americans or veterans, we’re Britain: The government provides health care, funding it through general taxes, and patients get no bills. For people who get insurance through their jobs, we’re Germany: Premiums are split between workers and employers, and private insurance plans pay private doctors and hospitals. For people over 65, we’re Canada: Everyone pays premiums for an insurance plan run by the government, and the public plan pays private doctors and hospitals according to a set fee schedule. And for the tens of millions without insurance coverage, we’re Burundi or Burma: In the world’s poor nations, sick people pay out of pocket for medical care; those who can’t pay stay sick or die.This fragmentation is another reason that we spend more than anybody else and still leave millions without coverage. All the other developed countries have settled on one model for health-care delivery and finance; we’ve blended them all into a costly, confusing bureaucratic mess.

Which, in turn, punctures the most persistent myth of all: that America has

the finest health carein the world. We don’t. In terms of results, almost all advanced countries have better national health statistics than the United States does. In terms of finance, we force 700,000 Americans into bankruptcy each year because of medical bills. In France, the number of medical bankruptcies is zero. Britain: zero. Japan: zero. Germany: zero.

Barack Obama’s health reform plan is similar to the Swiss model of insurance, even though the right wing hysteria claims it to be a socialized system like the British NHS.

Large pharmaceutical companies are known to have enormous influence in the US. They have also had a lot of influence on various international trade policies such as those on intellectual property, sometimes to the detriment of poorer countries facing health crises as described in the global health overview page on this web site. In the US, high drug prices have been an issue for many years, with some people even going across the border to Canada to get more affordable medicines.

On June 22, President Obama announced an agreement with big drug companies to cut the price of medicine by $80 billion. While that sounds like a large amount, according to investigative reporter Greg Palast, it is actually an agreement that drug companies will reduce the amount by which they increase their drug costs over the next 10 years, locking in a doubling of costs. US spending on prescription drugs projected by the government for the next ten years is $3.6 trillion, according to Palast, resulting in a very small saving — 2%, whereas most European nations are able to get 35-55% reduction and the US Veterans are able to get 40% reduction.

A combination of pharmaceutical companies, insurance companies, mainstream media and Republican opposition has seen organized (and often hysterical) opposition to the health reforms, branding it as communist/socialist (even though it is nothing of the sort) and against individual freedom due to subsidies and other policies being entertained (though such groups have rarely complain when the government—including Republican—has long provided other anti-free-market subsidies to various industries).

Obama appears to be losing the public relations battle, as journalist Bankole Thompson notes, writing for Inter Press Service, who adds that the media has given little or no information about the demographics of the polls being conducted, and whether respondents include the estimated one in three citizens who lacked health insurance at some point in 2007-08.

The much publicized hysteria against Obama’s reforms include claims that other industrialized nations systems don’t hold up to the American system, Britain being amongst the targets, much to the chagrin of British politicians and public in general.

Britain’s National Health Service

Britain has had a national health service (NHS) since the late 1940s. While tax-funded and government run, it provides access to all citizens and is mostly free at point of use.

The British system includes free primary care paying doctors and running hospitals through decentralized trusts. Side NoteIn fact, the NHS isn’t a centralized socialist bureaucracy that scare-mongering stories from the US right wing suggest; health authorities for different regions and local NHS primary care trusts allow local decision-making and accountability while the centralized NHS provides a framework and guidelines.

Almost all treatment is free. For working age citizens, prescriptions are obtained with a flat fee (with pharmacists often telling patients if the same drug is cheaper over the counter than through prescription). Dentist and optician visits typically have some fee associated with them, with dentistry having been increasingly privatized for many, many years.

There is a parallel private health option but is used by a small percentage of the population (usually the wealthy, by definition).

Over the years, the NHS has changed in various ways, but even the parties traditionally hostile to big government (the Conservative party) typically state (at least publicly) support for the institution.

There have been a number of problems within the NHS, which the right wing in the US are keen to expose (even if it includes exaggerating or bending the truth about NHS problems). Despite some on-going issues (as with all systems), the service provides universal care with generally low wait times, even as it faces budgetary constraints and changing social habits for which the health system wasn’t necessarily designed (just two examples being increasingly excessive alcohol consumption and obesity).

There are also concerns that under the guise of necessary reforms due to the effects of the global financial crisis, a privatization agenda is being pushed onto the NHS. SpinWatch, for example, claims that private healthcare companies have built a dense and largely opaque network of political contacts in the UK with one aim — to influence policy in their interests and get the reforms they want:

Using favorable terms such as freedom

and choice

, some of the reform plans have been intensely criticized, such as giving GPs (General Practitioners — also known as Family Doctors) more control over their budgets. At first glance this sounds ideal: localism and ground-up accountability. However, GPs themselves are worried about this because they have not been consulted on this plan as it would not just meant they have to also become accountants — without extra budgets to do this — but that they would end up having to ration limited resources and some people may not be able to get treatment as needed, while diluting the power of the NHS as a universal system throughout the country.

For an overview of health systems in various other countries, try the following:

- Universal Health Care, Wikipedia (last accessed August 30, 2009)

- Health care system, Wikipedia (last accessed August 30, 2009)

Health care in developing countries

Many developing countries also strive to provide universal health care. However, most struggle to do so, due to lack of sufficient resources, or inappropriate use of existing funds. Health inequality, therefore, is quite common.

Poverty is a major problem. In some developing countries health facilities have improved considerably, creating a health divide where those who can afford it can receive good quality care. Health gaps typically mirror equality gaps. For the enormous numbers of people without access to health, there is a terrible paradox: poverty exacerbates poor health while poor health makes it harder to get out of poverty.

As detailed further on this site’s global health overview page, policies such as the IMF and World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Programs through the 1970s and 1980s have reduced the ability of many poor countries—many African nations in particular—to provide health services for their populations.

The same ideology encouraging those inappropriate health policies have continued to this day and privatization has often been preferred by these international financial institutions even if they have been shown over and over to be inappropriate for developing countries.

Corruption is an ever-present problem (sometimes in wealthy countries too). Corruption not only makes the problem worse, but some policies have encouraged corruption, too, as has the lack of health resources.

Another issue that plagues some poor countries is brain drain

whereby the poor countries educate some of their population to key jobs such as in medical areas and other professions only to find that some rich countries try to attract them away. The prestigious journal, British Medical Journal (BMJ) sums this up in the title of an article: Developed world is robbing African countries of health staff.

(Rebecca Coombes, BMJ, Volume 230, p.923, April 23, 2005.)

In many poorer countries, the number of health workers such as doctors and nurses in proportion to the population can be small and in many rural settings, it can be very difficult for people to access services.

The issue of user payment at point of use is perhaps more important in poorer countries than the wealthier ones. In wealthy ones, other than the US, universal health care works such that even where people have to pay at point of use, in many cases it is affordable.

Around the world, however, the problem can be worse as the WHO notes:

Most of the world’s health-care systems continue to rely on the most inequitable method for financing health-care services: out-of-pocket payments by the sick or their families at the point of service. For 5.6 billion people in low- and middle-income countries, over half of all health-care expenditure is through out-of-pocket payments. This deprives many families of needed care because they cannot afford it. Also, more than 100 million people around the world are pushed into poverty each year because of catastrophic health-care expenditures. There is a wealth of evidence demonstrating that financial protection is better, and catastrophic expenditure less frequent, in those countries in which there is more prepayment for health care and less out-of-pocket payment. Conversely, catastrophic expenditure is more frequent when health care has to be paid for out-of-pocket at the point of service.

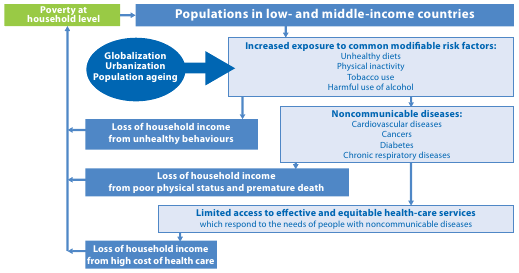

The way poverty and health costs are related, especially for the poor, cannot be understated. A WHO report on noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) — the leading causes of death worldwide — captures this very well.

This diagram summarizes the overall issues:

But their summary description is worth quoting at length:

The NCD epidemic strikes disproportionately among people of lower social positions. NCDs and poverty create a vicious cycle whereby poverty exposes people to behavioural risk factors for NCDs and, in turn, the resulting NCDs may become an important driver to the downward spiral that leads families towards poverty.

The rapidly growing burden of NCDs in low- and middle-income countries is accelerated by the negative effects of globalization, rapid unplanned urbanization and increasingly sedentary lives. People in developing countries are increasingly eating foods with higher levels of total energy and are being targeted by marketing for tobacco, alcohol and junk food, while availability of these products increases. Overwhelmed by the speed of growth, many governments are not keeping pace with ever-expanding needs for policies, legislation, services and infrastructure that could help protect their citizens from NCDs.

People of lower social and economic positions fare far worse. Vulnerable and socially disadvantaged people get sicker and die sooner as a result of NCDs than people of higher social positions … There is strong evidence for the correlation between a host of social determinants, especially education, and prevalent levels of NCDs and risk factors.

It is in this context that point-of-use health fees in poorer countries can be so catastrophic

, as the WHO continues:

Since in poorer countries most health-care costs must be paid by patients out-of-pocket, the cost of health care for NCDs creates significant strain on household budgets, particularly for lower-income families. Treatment for diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases and chronic respiratory diseases can be protracted and therefore extremely expensive. Such costs can force families into catastrophic spending and impoverishment. Household spending on NCDs, and on the behavioural risk factors that cause them, translates into less money for necessities such as food and shelter, and for the basic requirement for escaping poverty – education. Each year, an estimated 100 million people are pushed into poverty because they have to pay directly for health services.

The costs to health-care systems from NCDs are high and projected to increase. Significant costs to individuals, families, businesses, governments and health systems add up to major macroeconomic impacts. Heart disease, stroke and diabetes cause billions of dollars in losses of national income each year in the world’s most populous nations. Economic analysis suggests that each 10% rise in NCDs is associated with 0.5% lower rates of annual economic growth.

As also noted earlier, in developing countries, especially the poorest ones, a large portion of health funded is dependent upon external or foreign aid. However, some spending programs may divert from general needs to specific needs, such as building hospitals (as opposed to strengthening primary care), or funding for specific diseases (which is usually treatment based with less visible effort on preventative care), etc.

Despite improvements over time, as the above charts show, the challenge remains enormous. The WHO and others have identified many areas where health provision can be far more cost effective than is currently provided, even with severe budget constraints. Perhaps that at least can be hope for a healthier future.

As expensive as it may seem, health systems are an investment in people. Healthier people can contribute to the economy and society more easily, which for poorer countries is even more essential. But the structure of the health system, as well as spending, needs to be appropriate and take into account local conditions and constraints.

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated:

Global Issues

Global Issues